A photograph from 1994 captures Australian artist Emily Kam Kngwarray sitting cross-legged on the ground, wearing a purple sweater and a black beanie. In front of her lies an immense canvas, yet she is focused on a small section, delicately applying yellow paint with a long brush. The image conveys her deep concentration, embodying the meticulous care she invested in every piece of her work. “No gestural mark was ever a mistake,” says Kelli Cole, a curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the National Gallery of Australia. “There was intentionality in everything she painted.”

Born around 1914 in Alhalker, a community in the remote Utopia region of Australia’s Northern Territory, Kngwarray began painting in her 70s. Despite the late start, she became one of Australia’s most celebrated Indigenous artists, creating more than 3,000 paintings before her death in 1996.

This summer marks the first major European retrospective of her work, which will be showcased at the Tate Modern in London, following its presentation at the National Gallery of Australia in early 2024. The exhibition will introduce Kngwarray’s groundbreaking contributions to contemporary Indigenous art to a global audience. “This exhibition offers a chance to educate Tate’s audience on Indigenous culture and the diversity within Australia,” says Kimberley Moulton, co-curator of the retrospective at the Tate, alongside Cole. “Australia is home to over 250 different language groups, and this exhibition, while focusing on Kngwarray, also provides a broader context for understanding Indigenous identity.”

Though Kngwarray’s name is often spelled as “Emily Kame Kngwarreye,” the curators—both Aboriginal—chose to honor the version preferred by her community. “There was some controversy when the National Gallery first adopted the more common spelling, but as I always say, it was changed in the dictionary in 2010, and her community wanted it changed back,” explains Cole. “We made sure to use the correct spelling as we collaborated with her community for this exhibition.”

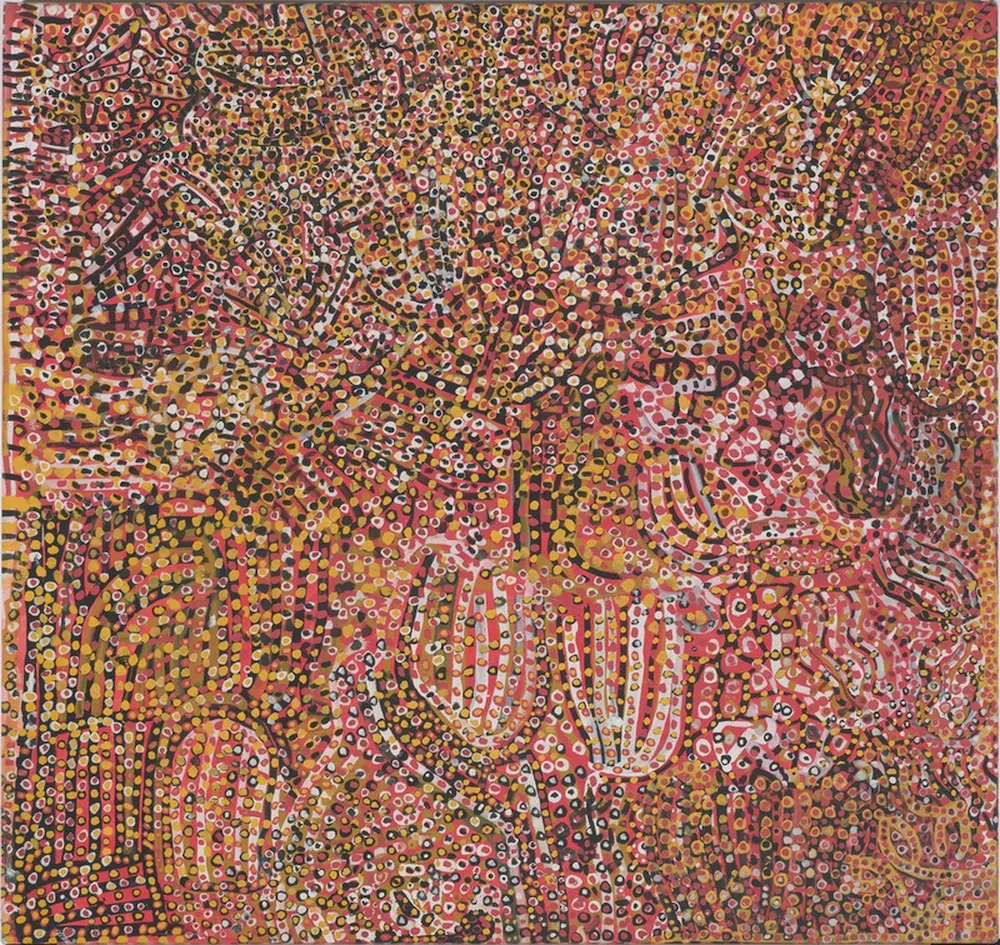

At approximately 20 feet wide and 9 feet tall, Earth’s Creation I (1994) is one of Emily Kam Kngwarray’s most iconic works, famously depicted in a candid 1994 photograph. The piece was not only featured in the main exhibition at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, curated by Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, but also made history in 2017 when it sold for $1.6 million (U.S.) at auction—setting a record for the highest sale price for a work by an Australian female artist.

Like many of Kngwarray’s paintings, Earth’s Creation I is recognized for its dynamic composition and bold use of color, achieved through her signature technique of layering dots of acrylic paint. “She cut her paintbrush in a special way, so when she dipped it in different colors, it created layered effects,” explains Kelli Cole. The artwork reflects Kngwarray’s deep connection to her Country—a term with a capital C used by Indigenous Australians to describe not just the land but also the water, sky, plants, animals, stories, songs, and spirits associated with it. In Kngwarray’s case, this connection is rooted in Alhalker.

While the imagery in Kngwarray’s works may appear subtle to those unfamiliar with Indigenous art and culture, much of her artwork represents specific elements of her Country. For example, Kngwarray, like many other artists, frequently incorporated the pencil yam (or anwerlarr in her native Anmatyerr language) into her paintings. The yam is not only a vital food source for the Anmatyerr people, but it also holds significance in “Dreamtime” or “Dreaming” stories—Aboriginal creation myths that are deeply tied to spiritual beliefs and cultural practices.

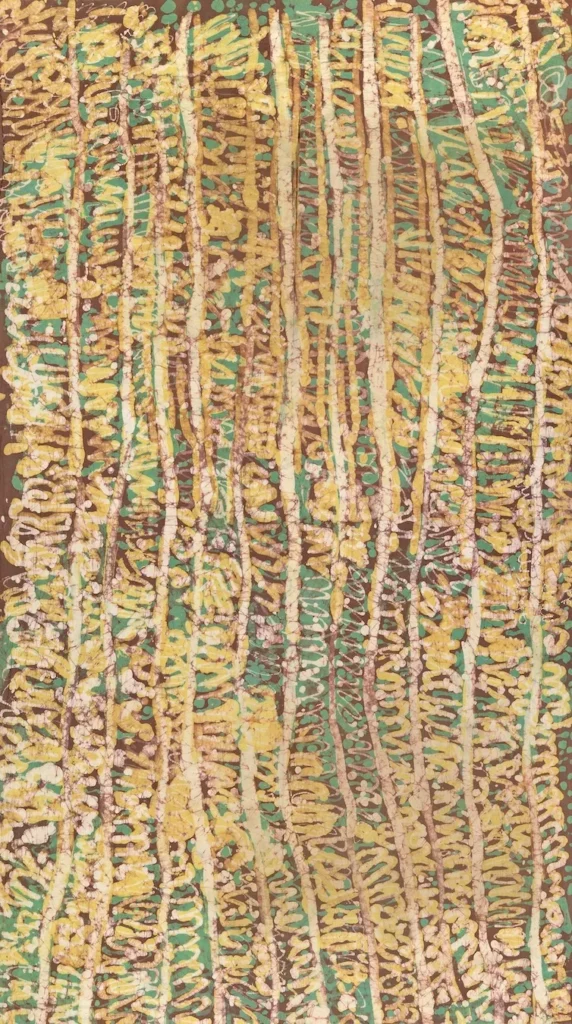

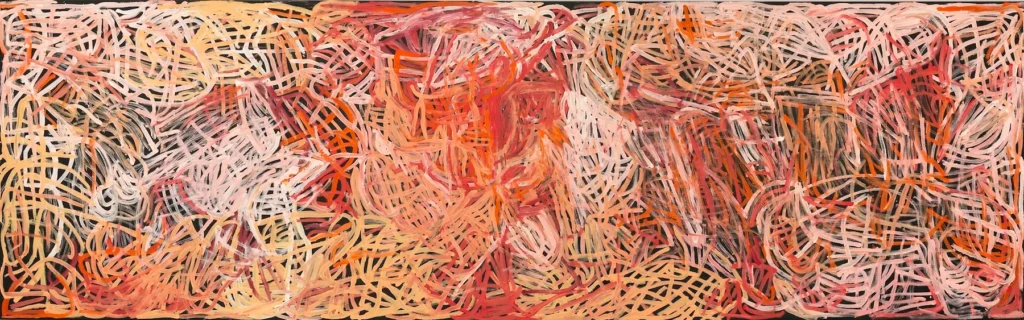

“Underneath those dots, a yam is always represented because that yam is so important to her,” Cole explains, noting that Kngwarray’s name, Kam—given to her by her grandfather—directly refers to the yam seed. (Her first name, Emily, was given to her by a “whitefella” when she was a teenager.) “Sometimes you can see the yam revealed in the underlayers of the paintings,” Cole adds. In works like Anwerlarr Anganenty (“Big Yam Dreaming”) (1995), Kngwarray depicts the yam’s underground network with flowing lines, such as white lines against a dark background, highlighting the spiritual and cultural importance of the yam in her art.

Before transitioning to acrylic painting, Emily Kam Kngwarray was introduced to batik alongside many other women in her community and became a founding member of the Utopia Women’s Batik Group. In 1988, she shifted to acrylic painting on canvas after an initiative called “A Summer Project,” organized by the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA), brought 100 blank canvases and acrylic paints to Utopia.

Much like many of her contemporaries, Kngwarray often found inspiration in the plants and animals of her homeland. In 1990, she was quoted saying that she painted a “whole lot,” listing distinct elements of her Country. “Arlatyeye (pencil yam), Arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard), Ntange (grass seed), Tingu (dingo pup), Ankerre (emu), Intekwe (plant that emus like), Antwerle (green bean), and Kame (yam seed),” she said. “That’s what I paint: whole lot.”

Kngwarray’s recognition has paved the way for many other Indigenous artists, particularly women, to gain the recognition they deserve. “Contemporary Indigenous artists are flourishing, from my perspective,” says multimedia artist Judy Watson, whose matrilineal family is from the Waanyi Country in Northwest Queensland. Watson, who exhibited alongside Kngwarray in the Australia Pavilion at the 46th Venice Biennale in 1997, notes the creativity and innovation of younger generations of Indigenous artists. “I see a lot of the young ones coming through who are very inventive,” she adds. “They are using so many different technologies and materials and being in the world.”

Thanks to the greater exposure of Indigenous art through artists like Kngwarray and the rise of technology, more people now see Indigenous artists for their talents rather than interpreting their work as anthropological artifacts from an unfamiliar culture. “It’s no longer this thing of this person from this Country,” Watson explains. “With more cultural exchange comes education, and with that comes respect.”

Although Emily Kam Kngwarray’s work is increasingly showcased in international spaces, it is important to remember that she created her art outside the influence of Western traditions. This makes comparisons to Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko problematic, as it risks overlooking the deep cultural heritage that shaped her work. “Everything she did was gestural, stemming from her painting on her body or drawing in the sand,” explains Kelli Cole. (In the awely ceremony, a ritual for women in Kngwarray’s community, women would paint their chests, breasts, and upper arms. Anmatyerr women also often drew lines and other shapes in the sand as a form of storytelling called typety.) “The movements of her hand are so innate, and they come from her Country,” Cole adds.

Judy Watson recalls the first time she saw Kngwarray’s work in a gallery. “It was laid out on the floor, and I just cried,” she says. “It was so beautiful.” Much like her approach to painting, Kngwarray would sit on the ground to prepare food, make tea, dig up yams, tell sand stories, and prepare for awely ceremonies. For Kngwarray, painting was deeply connected to the way she engaged with her culture daily. For Watson, witnessing Kngwarray’s art in this manner “felt like seeing, experiencing, and feeling Country,” she says, adding that it was an extremely emotional experience.