The Earth Partner Prize has always been less about polished eco-messaging and more about lived reality. In its 2025 edition, the award again turns the spotlight toward artists aged 14 to 30 who are translating climate crisis into images, narratives, and community action. The prize’s winners, announced in November and presented in connection with COP30 in Belém, feel united less by medium than by urgency. Their works don’t simply ask us to care about the planet. They show what it means to survive on it now.

A prize shaped by global youth voices

This year’s selection reflects a wide geographical spread, with many of the strongest voices coming from regions already bearing the brunt of environmental damage. The winning projects move between personal and collective scales. Some are grounded in a specific coastline or community. Others confront systems that profit from denial. Together, they read like a map of climate experience as young people live it: raw, inventive, and politically awake.

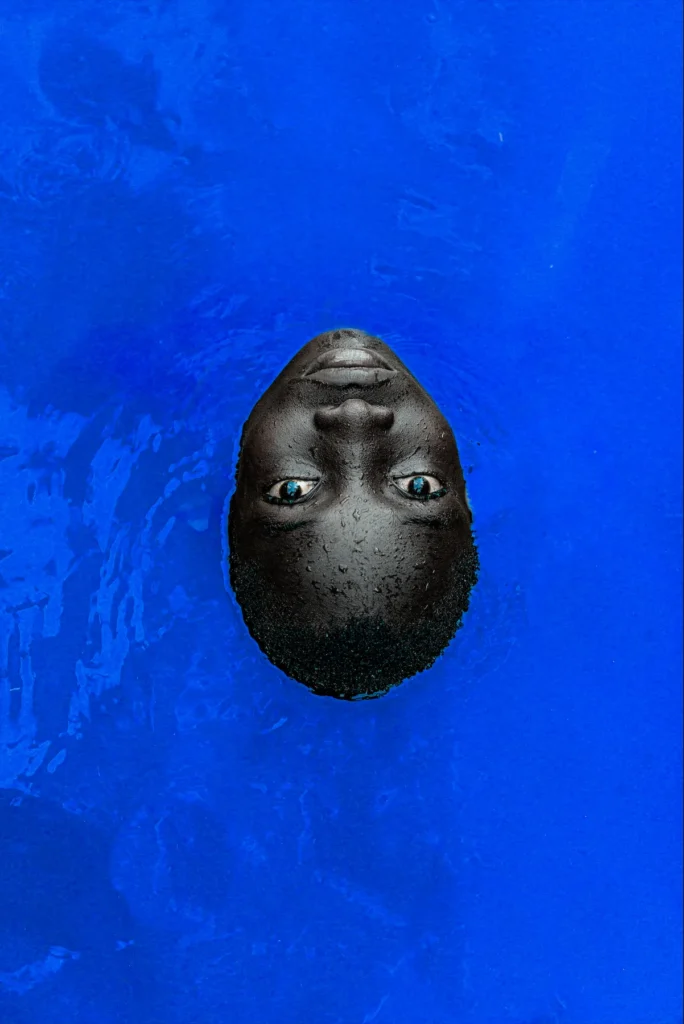

First place: Apah Benson and the Niger Delta’s poisoned paradise

Apah Benson, a photographer from Nigeria, won first place for his series The Last of Us. Shot in the Niger Delta, the work confronts oil spills not as distant statistics but as a daily, physical invasion. Benson’s images are saturated with color, yet the beauty is uneasy. Water becomes both lifeline and threat. Bodies appear suspended between play and peril, while the landscape carries the weight of extraction.

The series works because it refuses spectacle. Instead, it stays close to people who have learned to live inside environmental collapse. Benson captures resilience without romanticizing it, making the quiet violence of pollution impossible to look away from.

Second place: Two different warnings, one shared target

Second place was shared by two artists whose approaches could not look more different, yet meet in the same moral space.

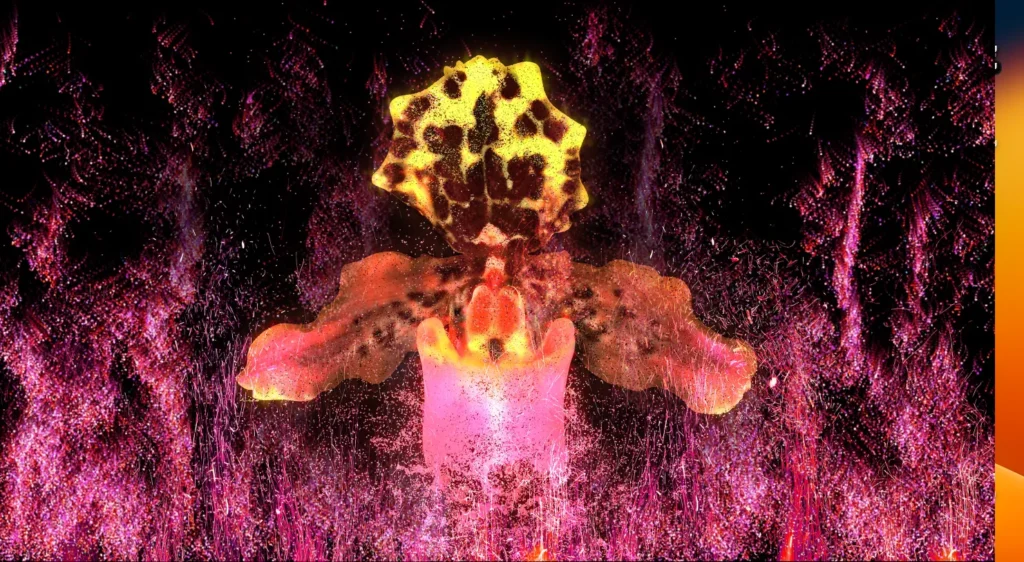

Abandokht Tohidi Moghadam, from Iran, was recognized for Something Suspicious, a stop-motion animation that skewers corporate greenwashing. Built from humble, tactile materials, the film exposes the way recycling rhetoric can become a cover for endless production and waste. The tone is sharp, almost playful, but its message is uncomfortably familiar.

Kyaw Zay Yar Lin, from Myanmar, received second place for Fishermen of Inle Lake, a photo series centered on traditional fishing practices in Shan State. The work is patient and observational. It honors a way of life shaped by water, technique, and community interdependence. In a year dominated by crisis narratives, Lin offers something rarer: a portrait of cultural ecology that still survives, and deserves protection.

Third place: Five visions of fragility and repair

The third-place winners form a rich chorus. Their works span continents but share a talent for finding meaning in what is vulnerable.

Yi Song, based between China and the UK, won for Archive of Fragility. The title alone signals a refusal to treat damage as abstract. Song’s work positions fragility as something worth documenting, not hiding, asking what we lose when ecosystems and human futures are treated as disposable.

Ruby Okoro, from Nigeria, was awarded for Circular Heroes, a photographic tribute to Lagos communities that transform lagoon waste into useful objects. Okoro doesn’t frame recycling as poverty-driven necessity. She frames it as ingenuity, labor, and pride, showing how circular economies already exist where people have had no choice but to invent them.

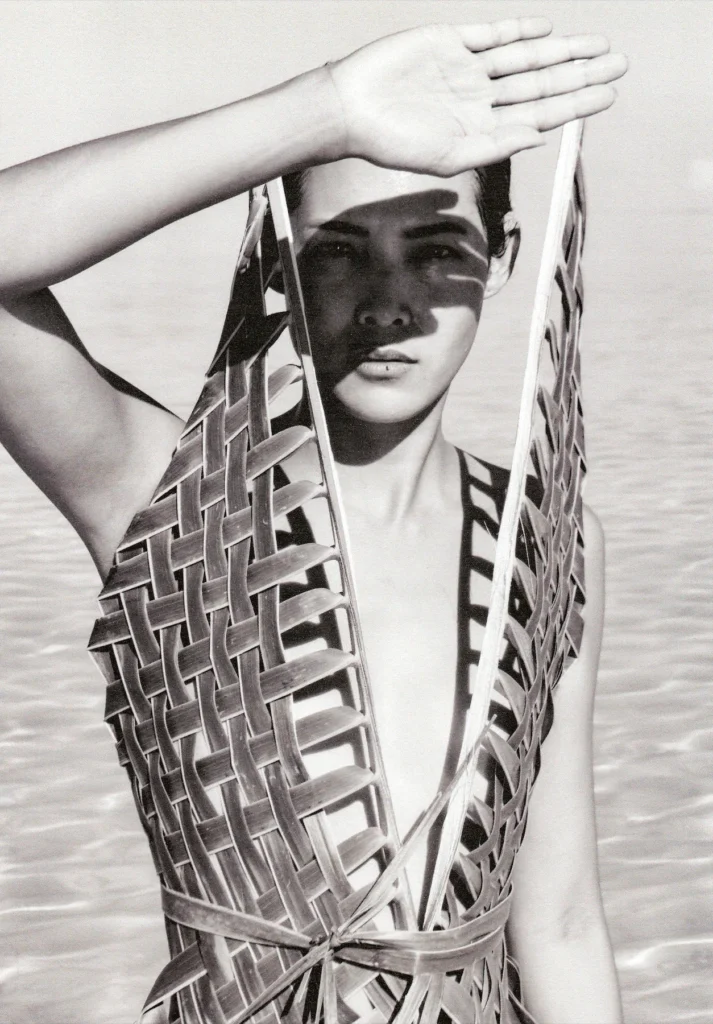

Igor Furtado and Labō Young, from Brazil, won for Island Time Forgot. Their series drifts between documentary and dream. Looking at the Cayman Islands, they trace how traditional, nature-based craftsmanship lingers within a landscape shaped by tourism and modern pressure. It’s a meditation on memory, myth, and the quiet sustainability embedded in ancestral making.

Andreu Esteban Sebastiá, from Spain, received third place for Without Warning. The work captures the sense of sudden rupture that defines climate reality for many young people: the idea that the world can change irrevocably in a single season, flood, or fire.

Tianxiao Wang, working between China and the UK, was recognized for The Sea Sustains Us. His images of Lembata Island in Indonesia hold a community at the edge of transformation. Whale hunting traditions, ocean ecosystems, and modernity collide. Wang documents that friction with empathy, showing climate change not as a future threat but as present negotiation.

The Impact Award: Climate art as community survival

Alongside the individual winners, the 2025 prize introduced an Impact Award. It went to Instituto Afro-Aurora Dance in Brazil for Dança Pajé: Favela Ancestral. The project focuses on artistic and ecological education through choreography grounded in Afro-descendant and Indigenous dance traditions. In a context marked by systemic violence, the work insists that culture is not decoration. It is a tool for dignity, continuity, and collective care.

Why these winners matter now

What makes this year’s Earth Partner Prize feel especially relevant is its tone. There is no glossy futurism here, no clean separation between “environmental” and “social” issues. Oil spills and greenwashing sit beside fishing traditions and grassroots recycling. The climate crisis appears not as one story but many, braided through labor, identity, colonial legacies, and neighborhood survival.

The winners remind us that youth climate art isn’t waiting for permission from institutions. It’s already mapping damage, honoring local knowledge, and inventing new ways to live. The Earth Partner Prize at its best doesn’t aestheticize catastrophe. It amplifies those who know it firsthand, and who are still imagining something beyond it.