Our list of the best artworks of the 21st century includes 100 pieces and 15,000 words.

There were many works that didn’t make the final cut, even though we still held them in high regard. Some were left out because the editors couldn’t reach a consensus on their value. Others were only thought of late in the process, after the list had already been finalized. And, of course, some just didn’t make the list due to space constraints.

However, in an effort to give a little more recognition to these overlooked pieces, each editor who contributed to the list has decided to defend one additional work that didn’t make the final selection. This isn’t an article about famous or universally admired artworks that were excluded—we know there are plenty of those. Instead, it focuses on works that editors feel strongly about, offering personal and passionate defenses for each.

Here are the justifications for a few more exceptional artworks.

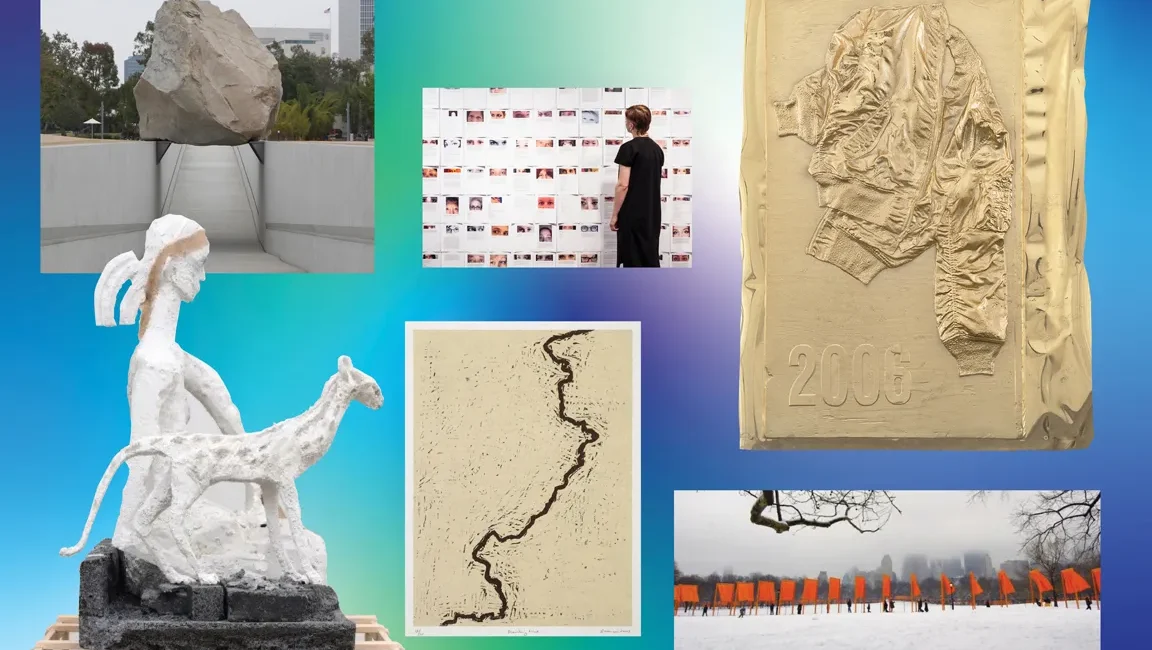

Michael Heizer, Levitated Mass, 2012

Standing beneath a massive 340-ton granite monolith, perched delicately on the edges of concrete walls and seemingly floating against the clear California sky, creates a truly sublime experience. Equally awe-inspiring is reflecting on the immense effort that went into the seemingly impossible task of placing such a massive rock in its current position. This monumental feat is the focus of Levitated Mass: The Story of Michael Heizer’s Monolithic Sculpture, a 2013 documentary that meticulously follows the journey of Heizer’s contribution to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The work involved was immense, from the artist selecting the rock at a Riverside County quarry to navigating the bureaucratic hurdles that arose during its transport on a specially built 206-wheeled truck, maneuvering across highways, bridges, and overpasses that were barely capable of supporting such a load. What I find most compelling about Levitated Mass is how it simultaneously celebrates the remarkable story behind its creation and plays with the spectacle of it all, maintaining a stoic, enigmatic presence that invites deep contemplation.

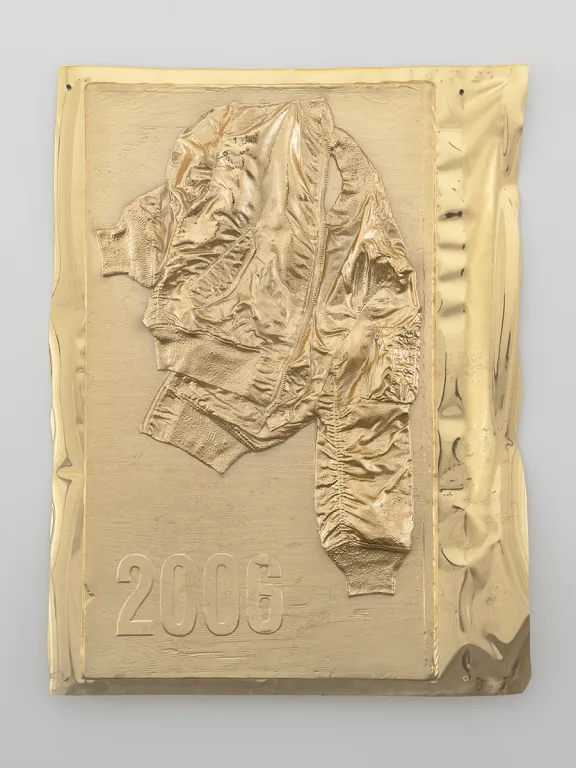

Seth Price, Vintage Bomber, 2006

I was really hoping this work by Seth Price would make it onto the list, where it stayed for a while before ultimately being pushed to the overflow section. Beyond the gold-toned, vacuum-formed polystyrene relief sculptures (like this one), Price’s diverse body of work spans a variety of media. It includes, among other things, a series of seemingly generic calendars featuring artworks by artists like Thomas Hart Benton, computer graphics, and more; music videos that pair found footage—ranging from computer animation loops to military, commercial, and news clips—with soundtracks of his own music and fairy tale readings; and a ready-to-wear clothing line (created in collaboration with fashion designer Tim Hamilton) using fabrics inspired by security envelope patterns. Crucially, it also features Dispersion, Price’s influential critical essay exploring art’s role within the broader landscape of distributed media—a vast, interconnected datascape defined by the flow of social information across platforms and devices in the digital era. Dispersal is a central theme in Price’s work—the bomber jacket, for instance, is both an icon and a symbol of dispersion, showing up in various forms across the 20th and 21st centuries as a marker of coolness and a catalyst for new, possibly subversive, approaches to art-making. —Anne Doran

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates, 1979–2005

It wasn’t until I volunteered to write about The Gates that I realized I had become open to reconsidering my previous opinion of the piece. When it was installed 20 years ago in Central Park, with 7,500 gate-like structures draped in flowing fabric, creating a 23-mile-long path, I shared the perspective of critics like Mark Stevens of New York Magazine, who described the work as a “visual one-liner” and pointed out that while the artists and their supporters called the color “saffron,” it resembled more of a Wal-Mart orange. However, looking back now, I’ve come to appreciate The Gates more. I’ve started to recognize the value in what a close friend of mine has been trying to convince me of for the past two decades: that the piece was quintessentially New York, deeply urban in its spirit; that it was placed in February, a time when winter was still hanging on but approaching its end, symbolizing a hopeful moment; that it merged an aesthetic experience of art with the natural world, evoking a sense of the sublime; that it offered both a space for reflection and a chance to heighten perception; and, most importantly, that it brought people together. —Sarah Douglas

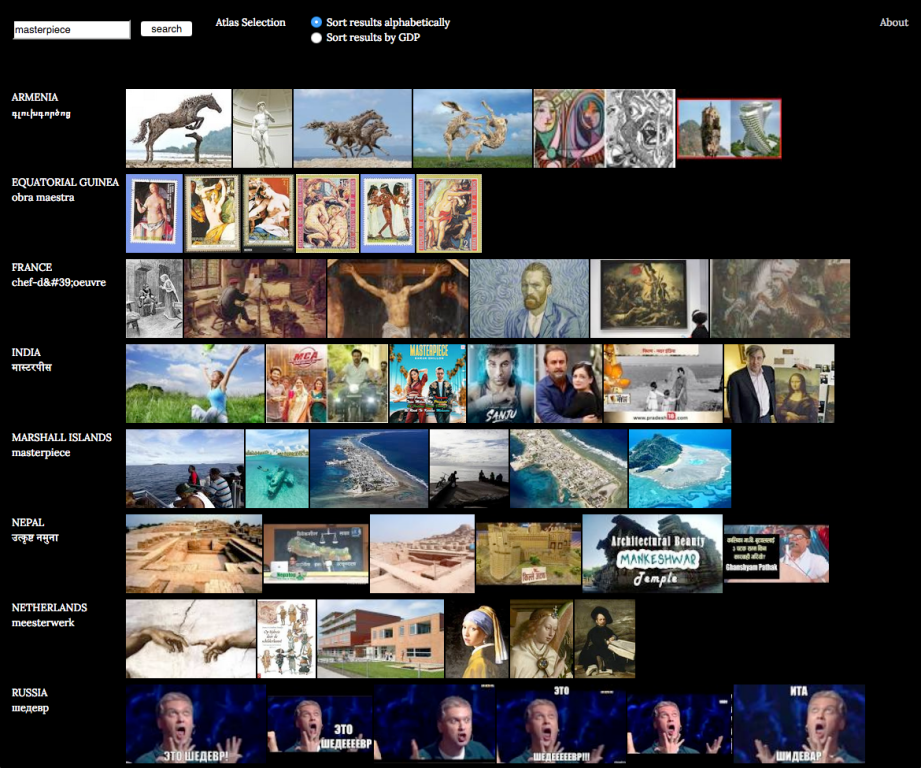

Taryn Simon and Aaron Swartz, Image Atlas, 2012

I still clearly remember when my editor first showed me Image Atlas in 2012. At the time, my understanding of net.art and digital art was limited, and I didn’t fully grasp that this collaborative project by artist Taryn Simon and computer programmer Aaron Swartz, commissioned by Rhizome, was a work of art. However, I was immediately captivated by its provocative concept. On a simple website, users would type a keyword—like “freedom fighter” or “masterpiece”—into the search bar, and the site would return the top five images from the most popular search engine in a given country (originally 17, now 195), based on real-time queries. These results could then be sorted alphabetically or by GDP. The images that appeared were often vastly different, shaped by each country’s unique cultural context. It’s easy to assume that we all access the same internet and receive the same search results—and this was particularly true in 2012. Image Atlas shatters that illusion, revealing that the internet is far from the objective, neutral digital landscape it’s often thought to be. Given the changes in the internet, search engines, and social media over the past decade, the work feels even more crucial to understanding our current visual culture than ever before. —Maximilíano Durón

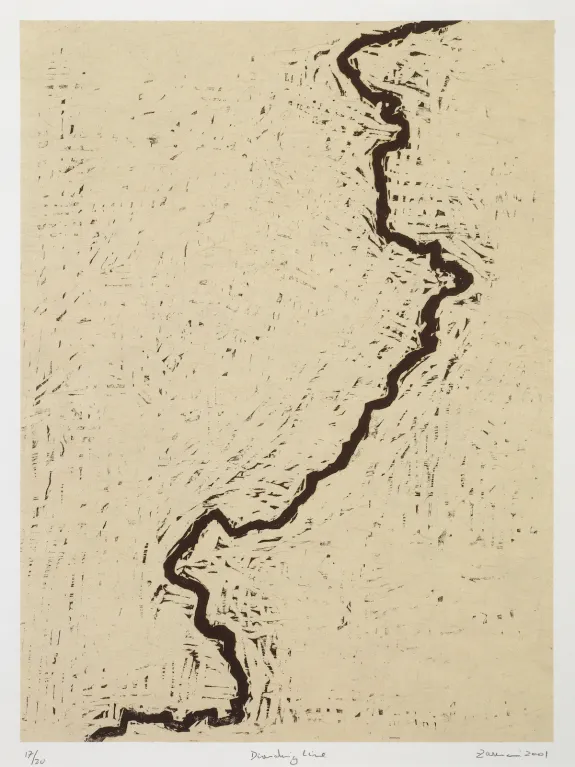

Zarina, Dividing Line, 2001

Geopolitical borders are often arbitrary, drawn by the powerful few and imposed upon others. This was the case in 1947 when the British violently partitioned India into two nations, creating what is now Pakistan. Zarina, like many Indians, was deeply affected by this event, known as Partition, which caused her family to be displaced. While the specific events of Partition are not directly depicted in Dividing Line, this woodcut is deeply marked by them, with the line itself acting as a stark, black scar across the white background. This slash alludes to the Radcliffe Line, the boundary established between India and Pakistan, though Zarina’s version of the line diverges slightly in form. She wasn’t aiming to replicate the Radcliffe Line exactly; rather, as she once said of this poignant print, “I don’t need to look at an atlas, the line is inscribed on my heart.” —Alex Greenberger

Yoko Ono, ARISING, 2013

Let me state for the record that, even after last year’s retrospective at the Tate Modern and with David Scheff’s biography releasing later this month, Yoko Ono remains underappreciated as an artist. While she is widely known to the public for her activism and protests alongside her late husband John Lennon, Ono should also be recognized for her groundbreaking participatory art, much of which carries a strong feminist message. One of her most powerful recent works is undoubtedly ARISING, first presented at Palazzo Bembo during the 2013 Venice Biennale. For this installation, Ono invited women of all ages to submit a “testament of harm done to you for being a woman.” ARISING has been displayed in various formats, but the most common is simple yet deeply impactful: the “testaments” are printed on A4 paper and either hung from lines or placed in a binder, each accompanied by an image of the woman’s eyes. Viewers are encouraged to quietly reflect on these testimonies, many of which recount experiences of rape, domestic abuse, and sexual molestation. Frequently written in the second person, these pieces address the perpetrators directly. The experience is overwhelming, both in the unique specificity of each testimony and in its painful universality. Long before the #MeToo movement, Ono recognized the vital conversation the world needed to have—and began opening the door to it. —Harrison Jacobs

Lin May Saeed, Girl with Cat, 2019

It seems that animal liberation will always struggle to gain traction, even within the left, where it is often pitted against human suffering—as though we can only care about one or the other. This is unfortunate, especially since the future of our planet may depend on it. Currently, the meat and dairy industries contribute a staggering 14.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and wild birds are dying in large numbers. However, Lin May Saeed understood that such uncomfortable truths were not widely accepted, so she took a more nuanced approach, appealing to her audience not with facts, but with “fables,” as she referred to them up until her untimely passing in 2023. One such fable is Girl with Cat (2019), a polystyrene sculpture depicting the titular scene. Drawing inspiration from the ancient Egyptians, who didn’t have a word for “animal” to separate nonhuman species, Saeed created an image of a young woman with a cat whose graceful form evokes the ancient Egyptian statuettes dedicated to the worship of cats. She paired the sculpture with a framed copy of Birgit Mütherich’s essay The Social Construction of the Other: On the Sociological Question of the Animal. Like much of her work, this piece subtly challenges the idea that human-animal relationships have always been as they are today, offering a quiet rebuttal to those who justify human domination of animals as “natural”—suggesting instead that these relations can, and should, be different. —Emily Watlington